Mikael Häggström, M.D. Author info – Reusing images- Conflicts of interest: NoneMikael Häggström, M.D.Consent note: Consent from the patient or patient’s relatives is regarded as redundant, because of absence of identifiable features (List of HIPAA identifiers) in the media and case information (See also HIPAA case reports guidance)., CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Why It Matters

If you work in surgical pathology, you’ll quickly learn that the journey from the operating room to the microscope is only as good as the tissue preparation along the way.

This article will first go over the different types of fixatives you may encounter in the pathology department, explain why they’re important, and finally outline what processing is and where it fits into a PA’s workflow.

In fact, fixation and processing are both core parts of a PA’s job; together, they directly influence how easily a PA can gross a specimen and, in turn, whether a pathologist sees crisp, intact structures or, conversely, smudged, unreadable tissue on their slides.

What is Fixation?

Fixation is the process of preserving fresh tissue, the tissue’s architecture and cellular details by stopping decomposition and enzymatic activity – it keeps the tissue from rotting or autolysing.

It uses a chemical, referred to as a fixative, to “fix” the tissue. Think of this as a way of chemically cooking it.

Common Tissue Fixatives in Surgical Pathology

Formalin (Clear)

Composition:

- 10% phosphate-buffered formalin (equals 4% formaldehyde; formalin is 40% formaldehyde in water; often referred to as NBF for neutral buffered formalin)

Indications:

- Standard fixative for routine fixation of all specimens

Advantages:

- Widely used in pathology departments and validated for special stains and immunohistochemistry

- Fixes most tissues well and is compatible with most histologic stains

- Can preserve tissue for months

Disadvantages:

- Fixation by protein cross-linking; even small specimens can require several hours

- Overfixation (days to weeks) can reduce immunoreactivity (partially reversible with antigen retrieval)

- Dissolves uric acid crystals (seen in gout) and can dissolve some calcifications if fixed over 24 hours (because formalin is a water based fixative and some crystals and calcifications are water-soluble.)

- Hazards: Eye, skin, and respiratory irritant. Classified as a human carcinogen (IARC)

- Strong odor; exposure must meet OSHA limits

- Requires additional PPE when handling large volumes or when adequate ventilation is not available

Non-Formalin Fixatives

Composition:

- Often alcohol-based; may have proprietary formulation

Indications:

- For avoiding formaldehyde exposure or for molecular studies (e.g., 70% ethanol fixation)

Advantages:

- Low hazard profile, no special disposal needed

- Often superior for immunoperoxidase studies due to absence of protein cross-linking

Disadvantages:

- Fixation time is critical — both under- and overfixation can harm results

- Poor penetration in large/fatty specimens

- Nuclear/cytologic detail may be inferior to formalin

- Some types suboptimal for estrogen/progesterone receptor studies

Bouin’s Solution (Yellow)

Composition:

- Picric acid, formaldehyde, and acetic acid

Indications:

- Any tissue, especially small biopsies

Advantages:

- Produces sharp H&E staining

- Helpful in identifying small lymph nodes (fat turns yellow, nodes stay white)

- Can decalcify tissue during prolonged fixation

Disadvantages:

- Makes tissue brittle if fixed >18 hours

- Large specimens become uniformly yellow, obscuring gross detail

- Lysed red cells, dissolved iron and calcium

- Reduced sensitivity for immunoperoxidase studies

- Hazards: Picric acid is explosive when dry; degrades DNA/RNA, limiting molecular studies

B-Plus (Clear)

Composition:

- Buffered formalin with 0.5% zinc chloride

Indications:

- Routine fixation of lymphoid tissues when lymphoproliferative disorder is suspected

Advantages:

- Rapid fixation with excellent cytologic detail

- Strong antigen preservation for lymphoid markers

- No special handling beyond standard formalin protocols

Disadvantages:

- Shares the same limitations as other formalin-based fixatives

Zenker’s Acetic Fixative (Orange)

Composition:

- Potassium dichromate, mercuric chloride, acetic acid

Indications:

- Bone marrow biopsies (8–12 hrs for decalcification)

- Soft tissue tumors with suspected muscle differentiation (fix 4 hrs)

Advantages:

- Rapid fixation with excellent detail

- Slowly decalcifies tissues

- Useful in pheochromocytomas for chromaffin reaction demonstration

- Lysing RBCs can improve visualization in bloody specimens

Disadvantages:

- Poor penetration; >24 hrs can make tissue brittle

- Requires post-fixation washing to remove mercury precipitates

- Poor antigen preservation for IHC; interferes with some enzyme stains

- Hazards: Mercury-containing — special disposal required; corrosive to metals; avoid skin contact

Glutaraldehyde (Clear)

Composition:

- Glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer

Indications:

- Electron microscopy specimens

Advantages:

- Excellent preservation of ultrastructural details

Disadvantages:

- Slow penetration; tissues must be cut into small cubes

- Requires refrigeration for storage

- May cause false-positive PAS stains

Alcohol (Clear)

Composition:

- Ethanol and methanol — rapidly displace water and denature proteins

Indications:

- Synovial specimens for suspected gout (preserves urate crystals)

- Smears, touch preps, and frozen sections (fixed in methanol)

Advantages:

- Preserves many antigens well

- No special disposal requirements

Disadvantages:

- Dissolves lipids, penetrates poorly

- Can shrink/harden tissue if left too long

- Requires precise fixation timing

What are you most likely to use in the lab?

Over the last 7 years I have regularly used only three of these:

Formalin for the majority of specimens, alcohol for gout specimens, and B Plus for bone marrow biopsies from people with possible hematological malignancies (aka blood cancers).

What Is Processing?

Processing removes water from fixed tissue and replaces it with paraffin (wax). This is one of the steps of turning the sections of tissue that a PA took into slides.

The tissue is ‘fixed’ when it’s put into formalin, which is the fixative. Processing is basically just dehydrating the tissue and infiltrating the specimen with paraffin.

Step 1: Fixation

- Purpose: Preserve tissue architecture and cellular details by halting decomposition and enzymatic activity. This also eliminates the majority of pathogens from the tissue (e.g. formalin kills bacteria and viruses)

- Most common fixative: 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF)

- How it works: Formaldehyde molecules cross-link proteins, locking cells in place

- PA relevance:

- Ensuring specimens are adequately opened and placed in enough fixative is one of the first steps you perform in the lab.

- Thin tissue slices (1-2 cm) allow formalin to penetrate evenly –> this is especially important for fatty tissue like breast specimens.

- Poor fixation can lead to autolysis (tissue breakdown), making microscopic interpretation difficult or impossible.

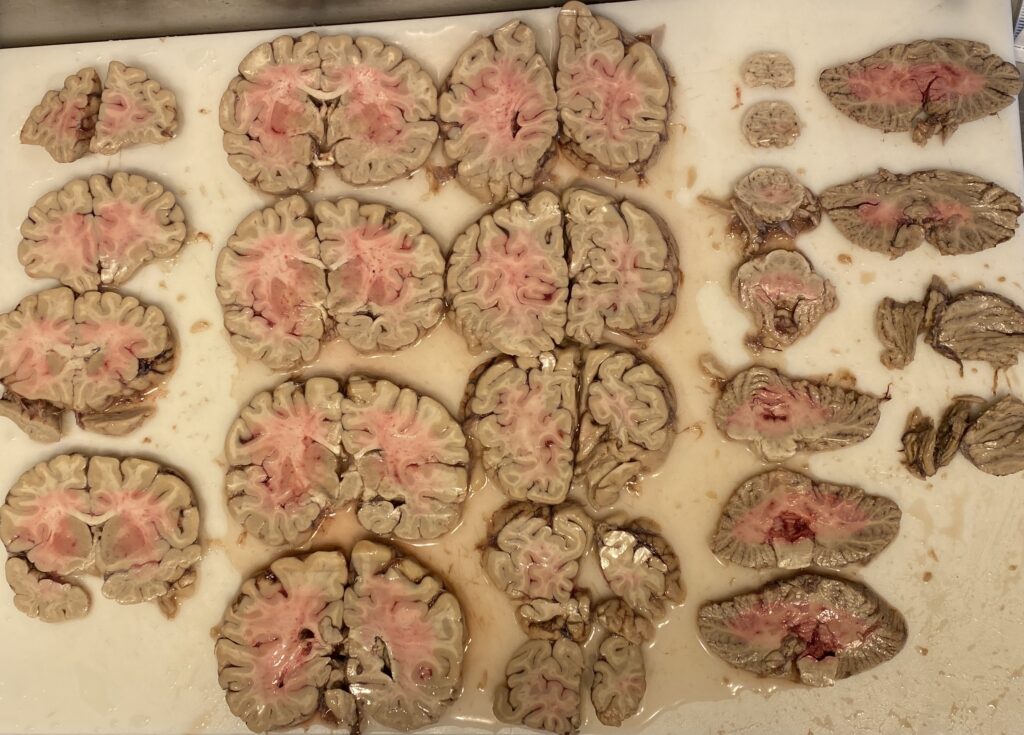

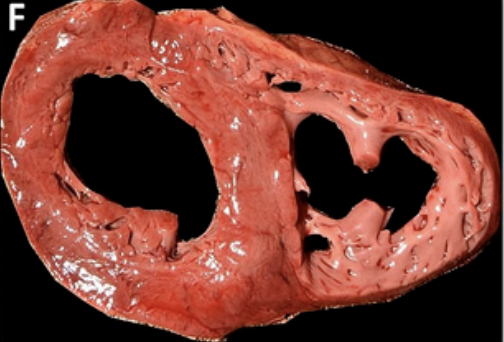

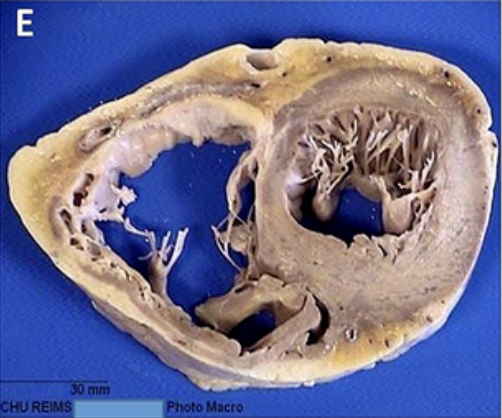

The pictures below show the difference between unfixed and fixed tissue. The first photo (F) is an unfixed cross-section of a heart. The second photo (E) is a fixed cross-section of a heart.

Fixed tissue is often pink or red in color, and its texture is normally soft and pliable.

Note the coloration differences in this fixed tissue. Muscle turns a dull brown color and fat turns pale yellow. The texture is also much firmer now.

Callon, D., Joanne, P., Andreoletti, L., Fornès, P., et al. (2024). Autopsy and histology patterns. A. Gross pattern… Figure from Viral myocarditis in combination with genetic cardiomyopathy as a cause of sudden death. An autopsy series, BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. via https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Autopsy-and-histology-patterns-A-Gross-pattern-case-1-B-Hypertrophic_fig1_380975214. Modified 2025.

Step 2: Processing

- Purpose: Replace water in the tissue (formalin is 90% water) with paraffin wax so it can be sliced on a microtome for microscopic examination

- Main stages:

- Dehydration – usually with increasing concentrations of ethanol to remove water

- Clearing – xylene or substitutes replace the alcohol and prepare tissue for paraffin infiltration

- Infiltration – melted paraffin wax permeates the tissue

- PA relevance:

- You won’t run the processor yourself in most labs, but you’ll need to understand the timeline and limitations as well as the basics of its operation

- Thick tissue blocks can process poorly, leaving the center unfixed and mushy – a common cause of slide artifacts

- Under fixed tissue won’t process properly which can cause time delays in getting slides to a pathologist for diagnosis

Common Fixation & Processing Pitfalls

| Problem | Cause | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Poor nuclear detail | Inadequate fixation time | Loss of chromatin clarity |

| Tissue falling off slides | Incomplete infiltration | Sections don’t adhere to slides |

| Smudgy or “washed out” H&E stain | Overprocessing | Excess exposure to clearing agents |

Trying to gross under fixed tissue can be technically difficult. Tissue that is unfixed is often softer and is sometimes just floppy compared to fixed tissue. This is great when the tissue is inside your body and needs to be able to bend, twist and move when you do, but when you are trying to gross something on and you need to cut a thin section of it, having something that is soft and floppy is hard to cut. Imagine trying to cut raw meat at home compared to cooked meat. It’s much easier to do this once the tissue is cooked (or in this case, fixed).

Fixation also means there is almost no concern of transmitting any sort of infectious substances to the grosser. With very few exceptions, formalin fixation will kill or inactivate bacteria, viruses, enzymes, and other pathogens that might normally be found in the tissue. This makes the tissue much safer to handle as a PA, especially if you ever accidentally cut yourself while handling a specimen.

Finally, once tissue has been fixed, identifying areas of pathology is often much easier compared to unfixed tissue. This is particularly true when having to dissect through fat to identify areas of tumor or lymph nodes. And this isn’t only a visual improvement – the textural differences that come from fixation can make identifying these much easier too.

Practical Tips for PAs

- Always ensure a fixative-to-tissue ratio of at least 10:1 when preparing fresh tissue for fixation.

- Open hollow organs (e.g. uteri, colons) to allow fixative contact with mucosa.

- For large or fatty specimens (e.g. breasts), bread-loaf or serially section to aid penetration.

- Communicate with lab staff about any specimens that need urgent processing or special fixatives (rush cases are often processed as soon as they are done fixing and certain tissues are put in fixatives other than formalin).

Further Learning

- Lester’s Manual of Surgical Pathology – Practical grossing and fixation guidelines.

- Carson’s Histotechnology – All the information you will ever need on fixatives and tissue processing.