- Introduction

- Hallmark Features of Necrosis

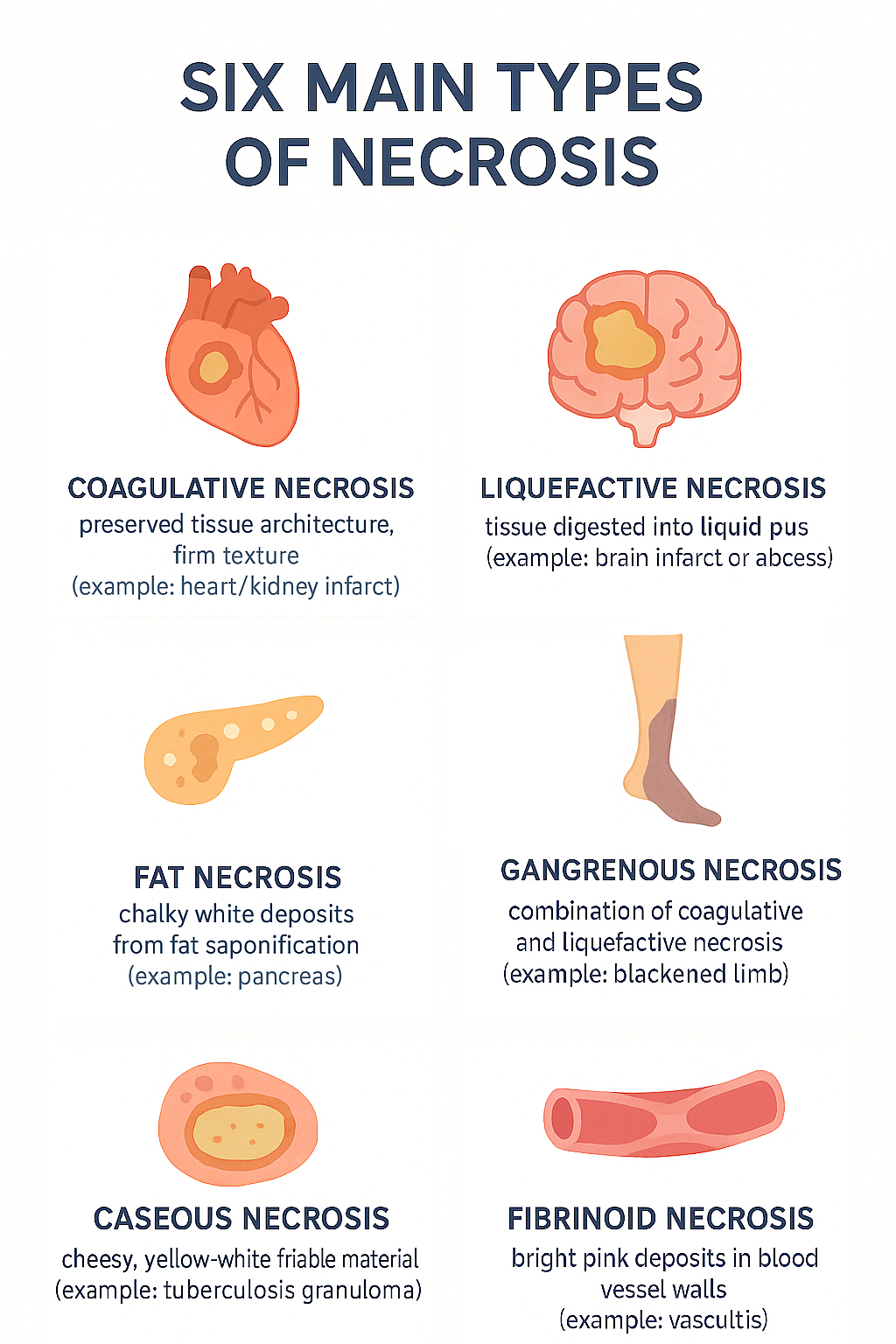

- Types of Necrosis

- Final Pathway: Clearance or Calcification

- Key Takeaways

Introduction

Necrosis is one of the most important cellular processes for pathologists’ assistants to understand. It represents accidental, unregulated cell death caused by lethal injuries such as ischemia, trauma, toxins, or radiation. When necrosis occurs, cell membranes lose integrity, intracellular contents leak out, and inflammation develops in the surrounding tissue.

This is in contrast to apoptosis, which is regulated cell death. In apoptosis, there is not the same type of collateral damage to surrounding tissue (aka inflammation) typically seen in necrosis.

| Necrosis | Apoptosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation | Unregulated (pathologic) | Regulated (programmed) |

| Inflammation | Yes (due to cell leakage) | No (tidy process) |

| Morphology | Swelling, membrane rupture | Cell shrinkage, apoptotic bodies |

| Cause | Ischemia, trauma, toxins | Physiologic or pathologic signals |

In this post, we’ll review the hallmark features of necrosis, including its nuclear changes, and break down the six main types of necrosis, where they are commonly seen, and how they look both microscopically and macroscopically.

Hallmark Features of Necrosis

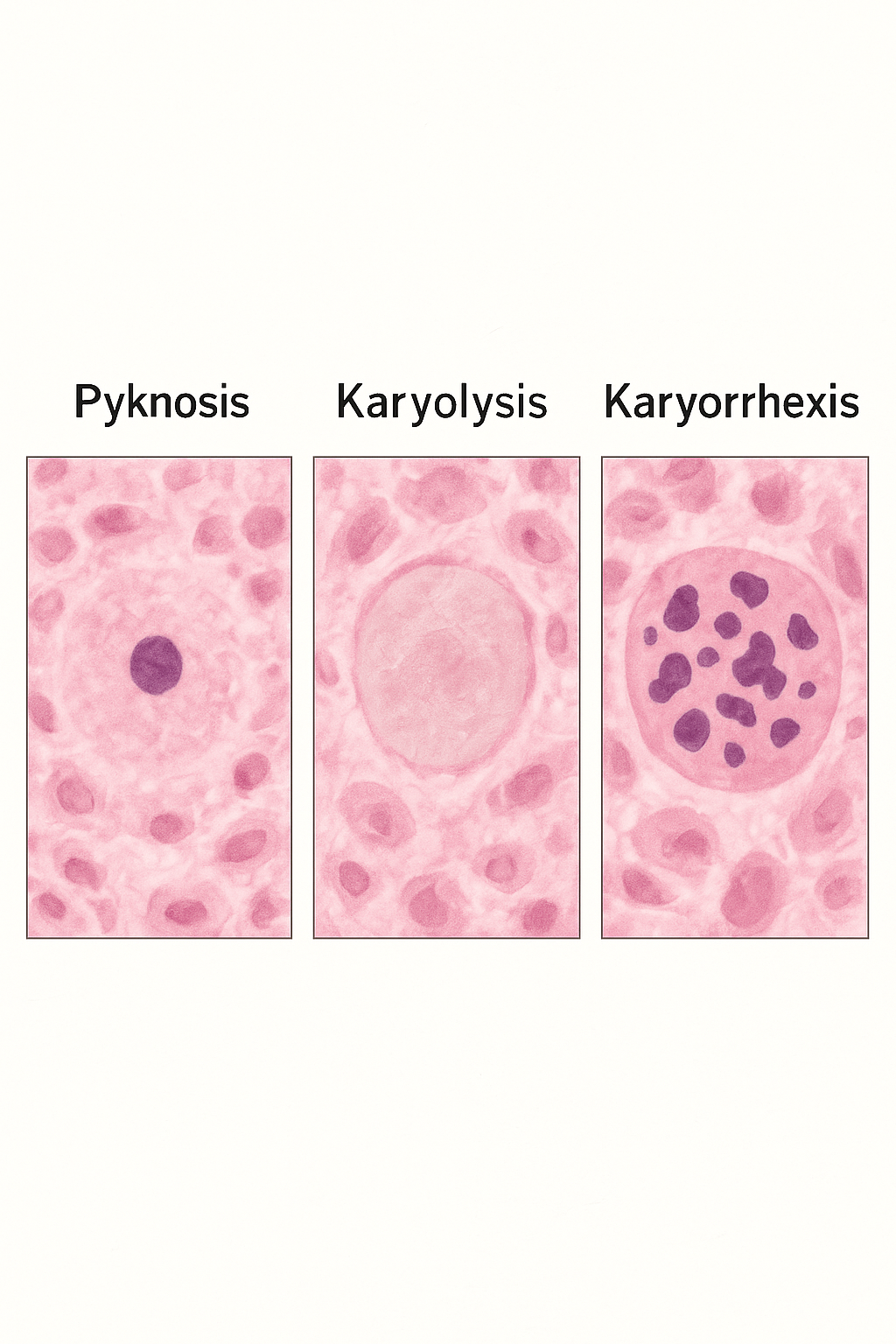

Nuclear Changes

Necrosis is defined by three characteristic nuclear changes:

Pyknosis – nuclear shrinkage and increased basophilia (dense, blue staining).

Karyolysis – fading of nuclear chromatin as DNA breaks down.

Karyorrhexis – fragmentation of the nucleus into the cytoplasm.

Together, these changes mark the irreversible death of a cell.

Tissue-Level Effects

When multiple cells die, the surrounding tissue or organ becomes necrotic. The exact appearance depends on the cause of injury and the cellular environment.

Types of Necrosis

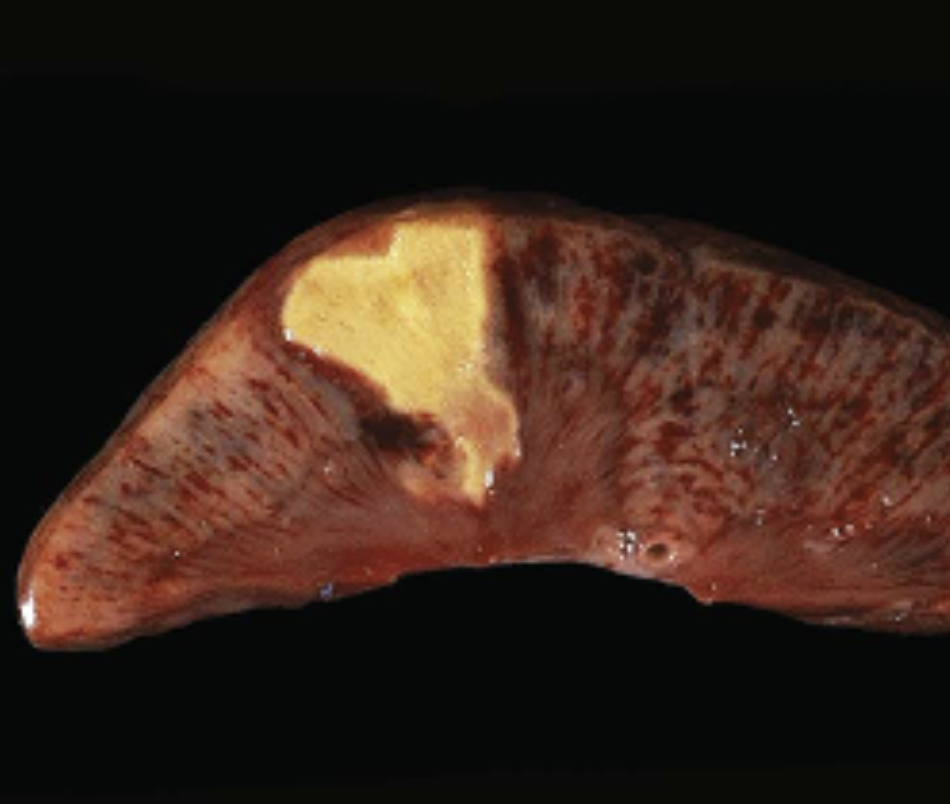

1. Coagulative Necrosis

- Cause: Ischemia or vessel obstruction. Eg) myocardial infarction

- Appearance: Firm tissue with preserved architecture (for a few days)

- Key Point: Injury denatures structural proteins but also enzymes → blocks proteolysis of dead cells

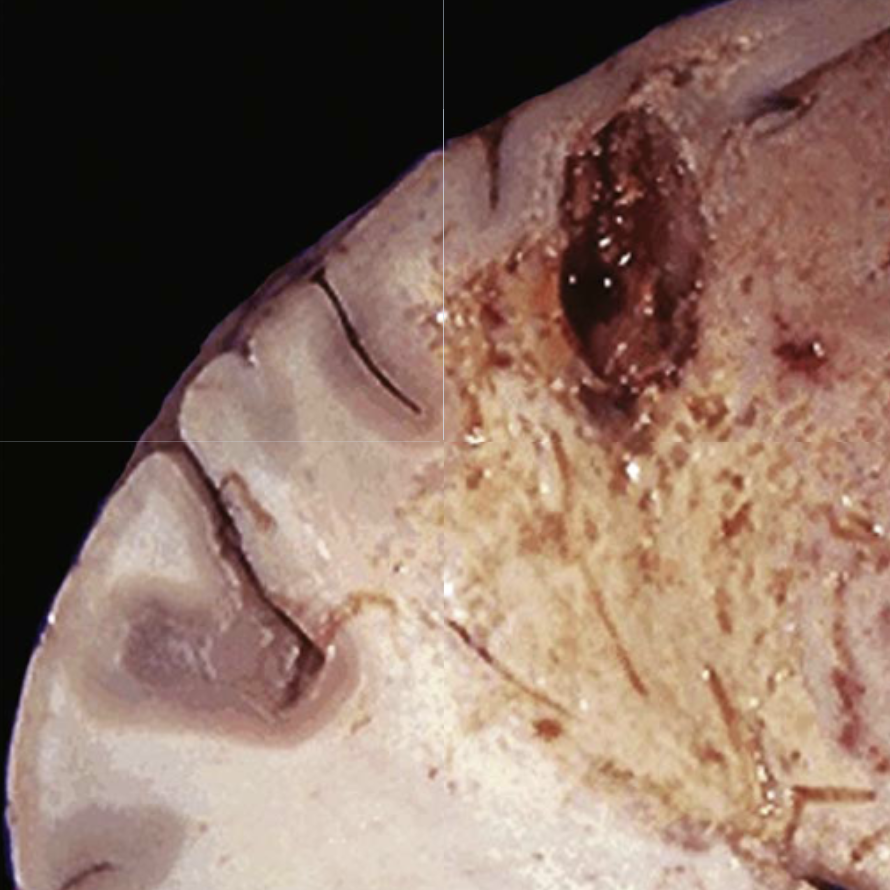

2. Liquefactive Necrosis

- Cause: Dead cells are digested and tissue becomes a liquid viscous mass. Eg) Cerebral infarct, abscess

- Appearance: Liquid mass, often creamy yellow (pus)

- Key Point: Classically seen in brain infarcts. Also seen with infections

3. Gangrenous Necrosis

- Cause: Severe ischemia of limbs (often legs) complicated by infection. Eg) Diabetic foot, frostbite

- Appearance: Combination of coagulative and liquefactive necrosis

- Key Point: Term commonly used in surgical and clinical settings

4. Fat Necrosis

- Cause: Enzymatic destruction of fat cells causes liquefaction. Triglycerides are split and combine with calcium . Eg) Acute pancreatitis after alcohol use

- Appearance: Chalky white deposits from fatty acids binding calcium (“fat saponification”)

- Key Point: Typical in acute pancreatitis

5. Caseous Necrosis

- Cause: A collection of fragmented, lysed cells and debris within an inflammatory border. Eg) Granuloma from tuberculosis

- Appearance: Soft, friable, “cheese-like” material within granulomas

- Key Point: Most often associated with tuberculosis

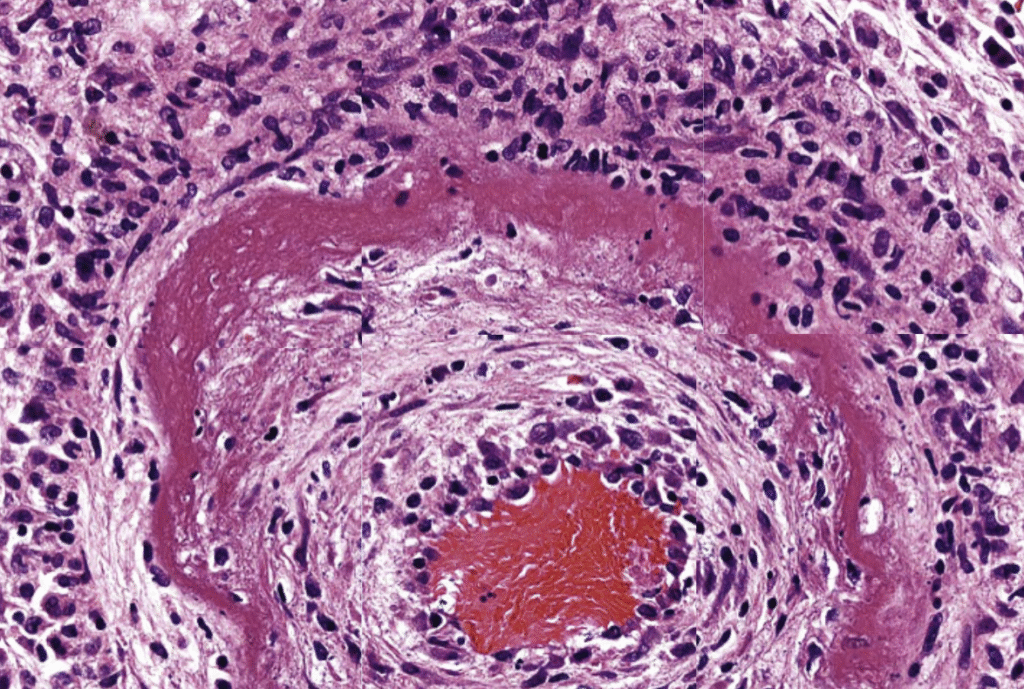

6. Fibrinoid Necrosis

- Cause: Immune-mediated injury to blood vessels with deposition of antigens or antibodies in vessel walls. Eg) Malignant hypertension

- Appearance: Bright pink (eosinophilic) deposits of antigen–antibody complexes and fibrin within vessel walls (seen on histology only)

- Key Point: Seen in vasculitis and severe hypertension

Final Pathway: Clearance or Calcification

No matter the type, necrotic cells are eventually removed by phagocytosis from leukocytes (like macrophages). If debris persists, it may calcify – a process called dystrophic calcification.

Key Takeaways

Dead tissue is either cleared by immune cells or calcifies if left behind.

Necrosis is irreversible cell death triggered by lethal injuries.

Nuclear changes (pyknosis, karyolysis, karyorrhexis) are diagnostic hallmarks.

The morphology of necrosis varies by cause – from firm tissue in ischemia to pus-like in infection or cheesy in tuberculosis.

Common causes include ischemia, infections, fat digestion, and immune reactions.